Much ado about Interlinguistics

Interlingua activists and Toki Pona inventor react to an interview in Esperanto referring to the two languages

UPDATES appear in this font style, preceded by: ‘UPDATE: [date]’.

Disclaimer: This article is in English, as, paradoxically, English is somehow neutral when we deal with different invented languages, as in this case.

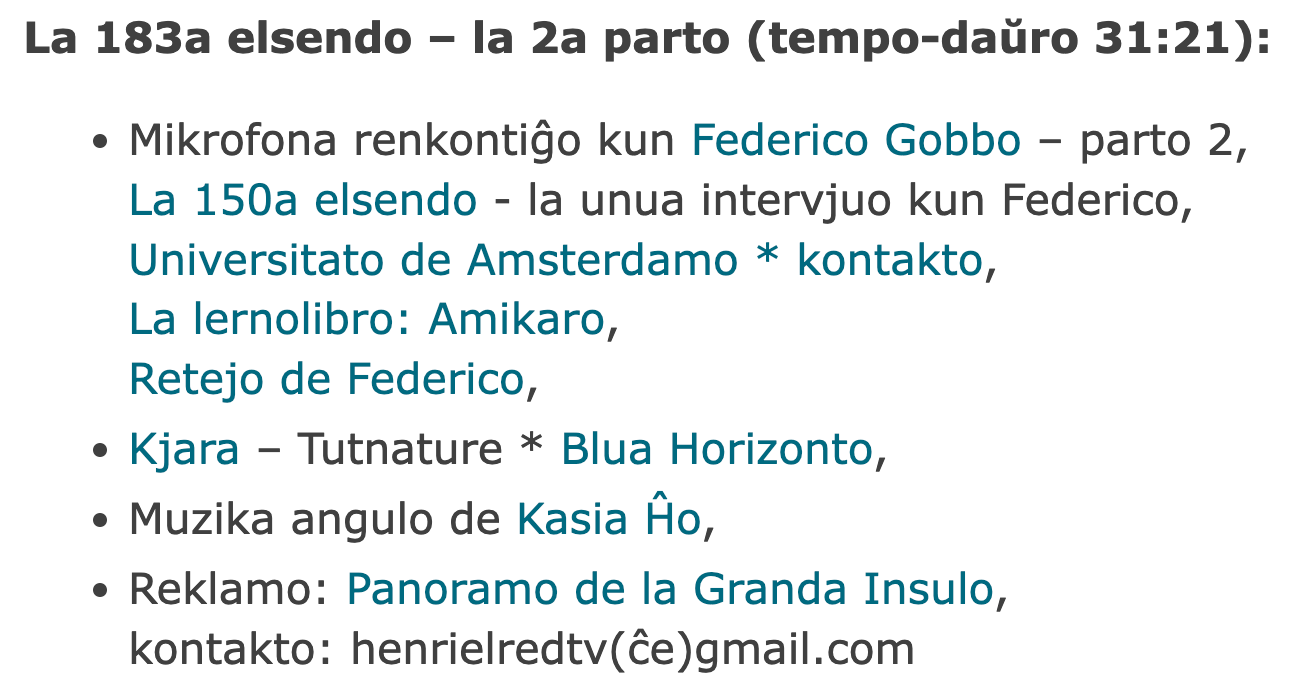

On February 26, 2025, an interview of mine was published on Varsovia Vento, probably the most popular podcast in Esperanto worldwide. It is completely independent of podcasting platforms, so its popularity is an educated guess of mine, having been a long-time observer of the Esperanto phenomenon, both online and in the real world. Immediately below, there is the description of the second part of the podcast, where the interview appears:

As you can see, there is no emphasis whatsoever on the short mentions of invented languages other than Esperanto. After all, the Special Chair I hold at the University of Amsterdam is devoted to Interlinguistics and Esperanto: it is perfectly normal that Esperanto has a special place within it. I could not imagine in advance that my interview would generate reactions outside the Esperanto community. But that was what happened. In particular, by IALA’s Interlingua activists and Sonja Lang, the inventor of Toki Pona.

A Facebook group with my comments cancelled

All scholars interested in Interlinguistics should follow the main (online) places where activists of major invented languages gather, and I am no exception. For this reason, I am enrolled in the Facebook group devoted to Interlingua. Immediately below, the screenshot of the home page of the group today (March 30, 2025):

Approximately 1,900 members in a Facebook group is a remarkable number for Interlingua, as the total number of active Interlingua users is perhaps 100 worldwide. Even at its peak, Interlingua never reached the important benchmark of 1,000 activists. I say so, taking as my source an internal account of the first 50 years of this language's history, since its publication, a self-published book written in Interlingua — not surprisingly — by Ingvar Strenström, “the tireless ambassador of Interlingua”. What struck me in reading it is that, after the historical role of Alice Vanderbild Morris, the main force behind the IALA, the history of Interlingua is 95% a history of men only.

In the interview for Varsovia Vento, Irek, the interviewer, provoked me asserting that Interlingua, once upon a time a major “rival of Esperanto” — expression by the sociologist Roberto Garvía put as a title in one of his scholarly books, ‘disappeared completely’. In my answer, I amended his trenchant judgement with an ‘almost’. Immediately below, the post in the Facebook group reporting the two lines (in Esperanto and in Interlingua), with the allegation that this is a ‘very disconcerting news’ (my translation from Interlingua):

Later, I replied to some of the comments that criticised me or my results, but they were cancelled. As one of the main arguments of Interlingua is that ‘through Interlingua you understand many languages. News, websites and texts in French, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese are understandable. The world expands.’ (my translation of the section Comprende le mundo in interlingua.com) I did a little experiment, answering in Italian, which I am a native speaker of (to simplify a rather complex multilingual background, but for the sake of the argument, it works here). In one of the replies, I read a complaint that the writer had to open a dictionary to understand an expression I used. It is a pity that the conversation was erased! Perhaps I violated the rules of the group, immediately below:

Be what it is, my estimate of 100 active users of Interlingua is confirmed by a prominent activist, Ruud Harmsen, who commented: ‘he is right, isn’t he? The number of *active* speakers of Interlingua (…) are perhaps 100 in the whole world. No more.’ Immediately below, the original comment in Interlingua, it is the first one on top.

My argument, which I published in many scientific publications — for instance, in the so-called ‘coolification paper’ by some of my colleagues — is that an invented language moves out of its project phase and enters the awakening phase through the development of its community of practice.

In the early stages of the awakening, community members (1) use the language more in writing than in speech, and (2) the main domain of use is self-reflection, meaning that they meta-reflect on the language. Interlingua is no exception. Immediately below, a post published two days ago, to explain this important point:

Basically, the post asks for an adequate translation in Interlingua of the English pair ‘girlfriend/boyfriend’ — please note that no consideration of non-binary relations is included here.

UPDATE on May 12, 2025: I received an email written in model Esperanto by the author of the post above on Saturday, May 12, 2025, which I read today. Basically, the author requested to be anonymised and also they suggested there was no consideration for non-binary identities by them, and that this is unfair and incorrect. The post is in a public FB group, and the author fully takes responsibility for its content, without any change, I read in the email message. I explain myself better. The post is a missed opportunity to include solutions for non-binaries; in Spanish, one of the source languages of Interlingua, people is saying ‘amige’ to include them beyond ‘amigo’ for masculine and ‘amiga’ for feminine. If I were an Interlingua activist (I am not), I would have included as a suggestion at least ‘amico/a/e’ and ‘fidantiato/a/e’ on the model of Spanish — actually, Occidental already had this solution, with the -e ending for unmarked nouns for the grammatical gender. That was my point. The post (and the discussion below, at least before this article was out, so I was not addressing the author only) doesn’t mention such an essential point, I mean, non-binary lexicon, anywhere. A matter of fact.

The answer is by Martin Lavallée, who, according to the Wikipedia article about him in Esperanto (containing more information than the versions in Ido and Interlingua, by the way)

‘is a Canadian Esperantist and Interlingua activist. He became Idist in 1997, he left the Auxiliary Language Movement for some years, and since 2010, he is active for Interlingua. He has a relatively good command of Esperanto and Interlingua. He is a member of the orthodox Bahai Faith.’

And you can see from the discussion that he is accused of proposing a lexical solution that is too similar to the Esperanto koramik(in)o.

This is an example of the domain of self-reflection in language use: talking about the language itself. How to translate a word, how to express a new concept, how a grammatical feature should be used correctly: all these are examples.

Of course, this does not mean that you can’t use words for doing things. It simply means that most of the time, invented language activists use the language to reflect on it instead of producing cultural artefacts in the language.

This is the main difference between all invented languages, different from Esperanto: even if self-reflection never fades away, the domains of use in the case of Esperanto are many and varied, because its community of practice is large enough to permit that.

What I said about Toki Pona explained in full

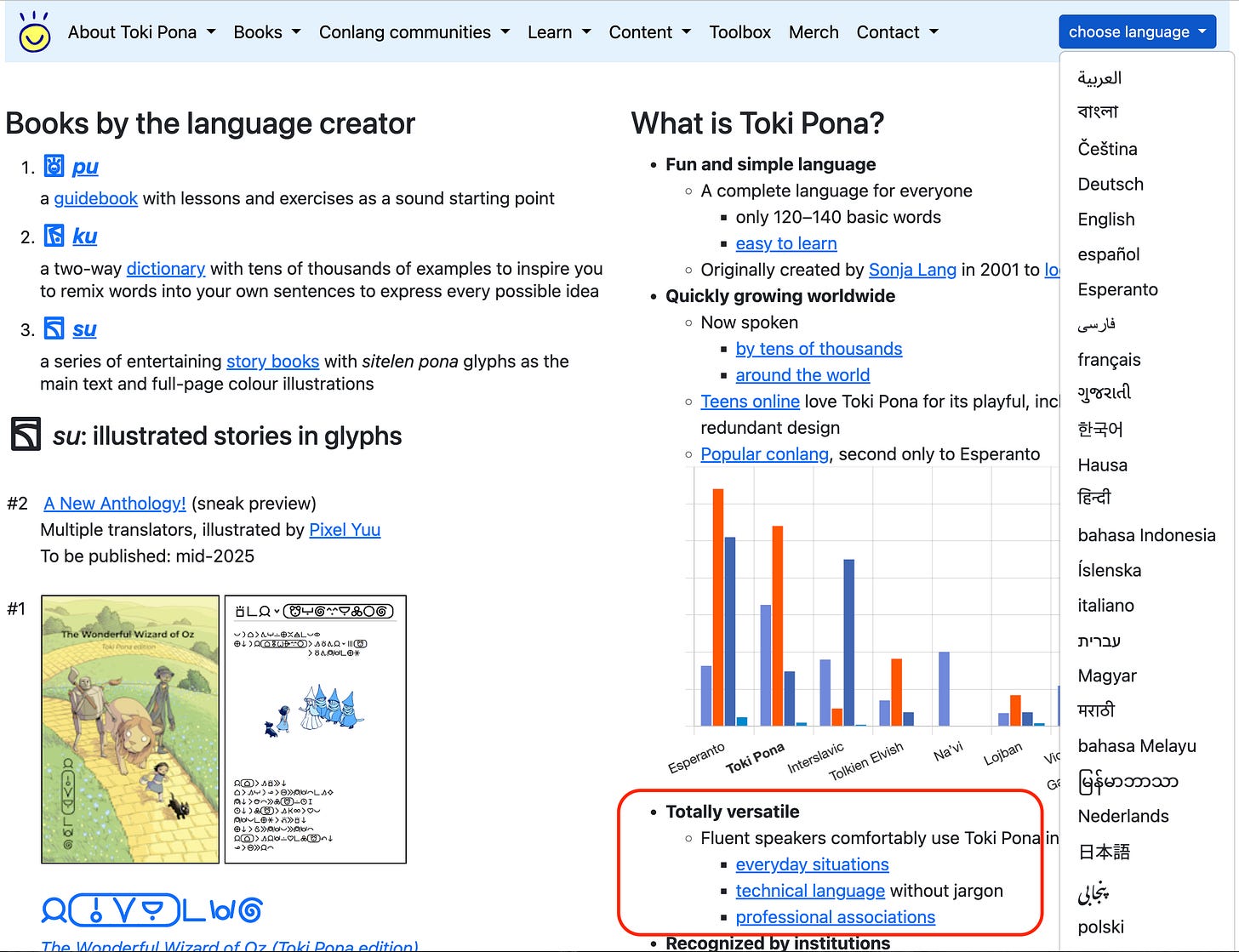

The second reaction after the interview in Varsovia Vento comes from the very language inventor and main activist behind Toki Pona, Sonja Lang. Immediately below, a screenshot of the website tokipona.org, which presents itself in a remarkable number of languages (Esperanto included, Interlingua excluded).

UPDATE on May 1, 2025: Sonja Lang informed me today (May 1, 2025) that now the web page in tokipona.org devoted to Conlang Communities includes Interlingua too — and I also spotted Ido, Glosa, and other new entries.

My emphasis (rounded square in red) is on the fact that the website informs you that you can use Toki Pona to express anything, despite the fact that the basic words are a bit more than 120 — for a comparison, 90% of the Italian texts are made by 2,000 lexical units, the so-called lessico fondamentale, the fundamental lexicon. Immediately below, my source, coming from the prestigious Enciclopedia Treccani.

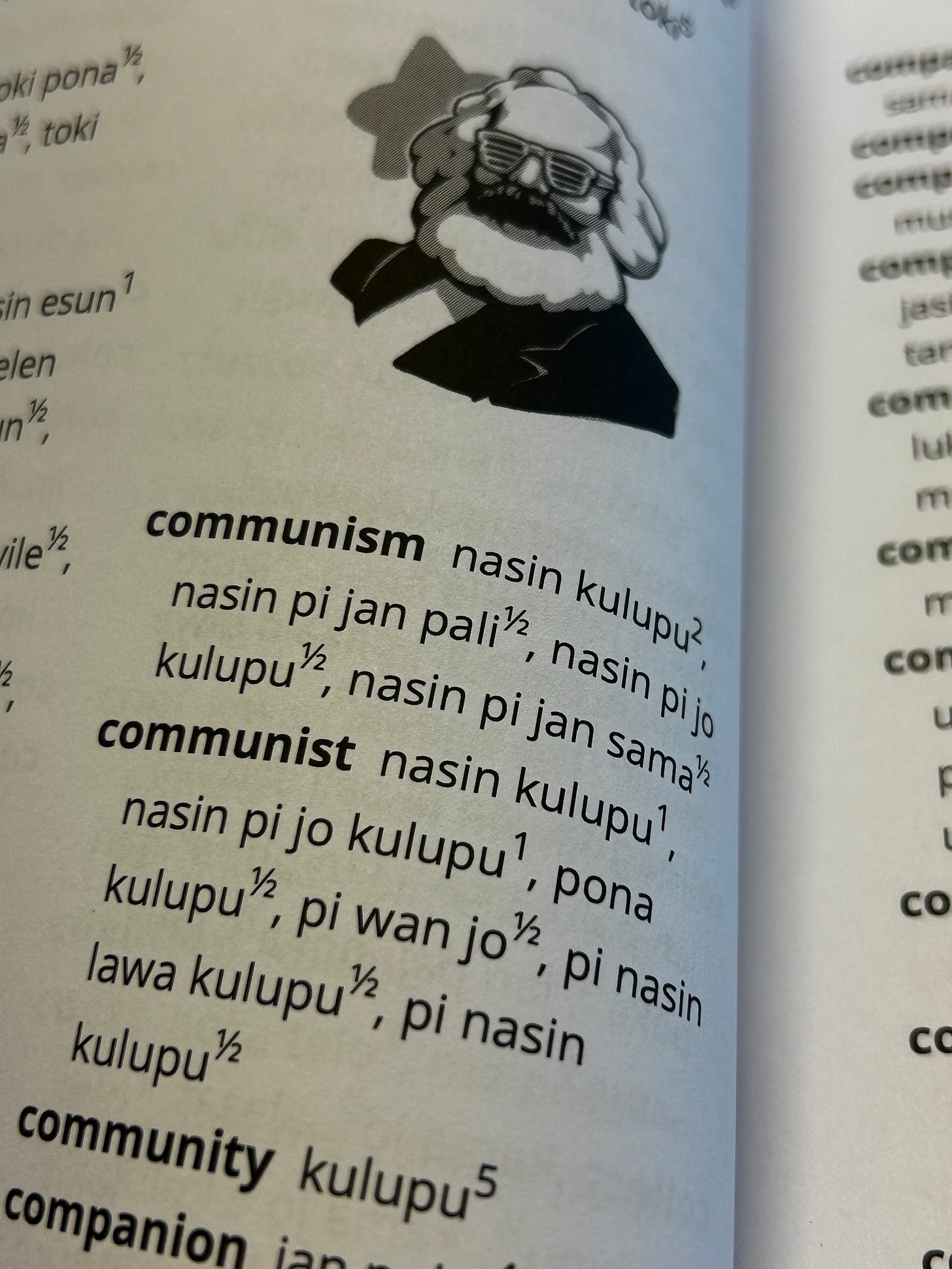

Please note that Toki Pona relies a lot on pragmatics, as one lexeme may have many different meanings. According to her Toki Pona dictionary, ‘community’ is kulupu, while both ‘communism’ and ‘communist’ have, as the first meaning, nasin kulupu (nasin meaning ‘doctrine’ and similar). Immediately below, from page 58 (note the post-modern portrait of Karl Marx):

In a section devoted to the de facto alliance between Esperantists and Toki Pona enthusiasts (the two groups partially overlap), Sonja Lang writes, in particular:

In the 2nd part of a Varsovia Vento podcast (Feb 2025), the host Irek Bobrzak and Federico Gobbo spoke in Esperanto about the emerging Toki Pona phenomenon in the world. They were aware of Toki Pona’s recent viral growth even among the youth at international Esperanto events, who enjoy singing in Toki Pona. They seemed unaware of how advanced speakers use it for all sorts of situations besides talking about Toki Pona. Federico appreciated the beauty of Toki Pona’s culture and values. From the very beginning, Sonja clarified that it’s not a rival to Esperanto, and she granted a lot of creative freedom to the speaking community.

I want to clarify my thinking better here: I am not ‘unaware’ that fluent speakers of Toki Pona may use it for many domains; my point is that, in its current state of awakening language, Toki Pona is still mainly used for self-reflection, rather than for doing things with words.

What amused me, is that Sonja Lang attributed to me and Irek, the interviewer, the role of the voice of the Esperantists. Immediately below, the title of such an attribution.

UPDATE: on May 1, 2025 Sonja Lang informed me that the title and introductory words were updated, and sent me the following screenshot:

I translate into English the most relevant part here of the interview extract, with clarification in italics:

“I learned to read some texts [in Toki Pona] but no, I am not interested in actively speaking it, as the main limit of Toki Pona, in my opinion, is that one speaks in Toki Pona about Toki Pona [I would add now: mainly]. This is, in a sense, Step 2.

Step 1 is publication.

Step 2 is speaking about the language in the language.

And you have to reach Step 3: talking about something else in the language.

Ha ha ha! And this still… Perhaps Toki Pona will never reach it [I would add now: because of the lack of critical mass]. And it doesn’t matter. But this is relevant news, as it is admitted, that this is a purpose of its own, without pretending anything else.

And this is, in my view, the nice side of the invention by Sonja Lang, as she said it immediately. And it gives a lot of freedom to the Toki Pona users. And this is a nice thing!”

I am glad to have seen our conversation in Esperanto transcribed and translated into Toki Pona. And I learned something new of me: that my name in Toki Pona is Peteliko :)

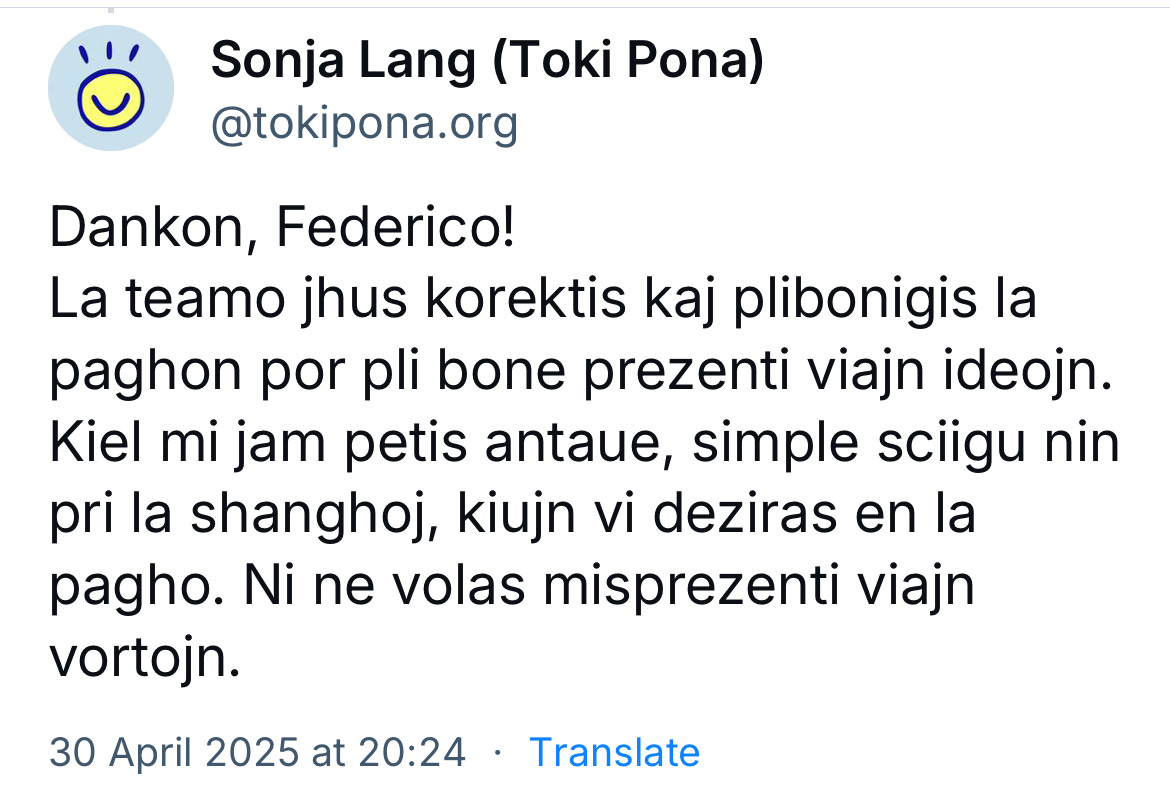

UPDATE on May 1, 2025: Sonja Lang offered me the possibility of amendment of my words there, via an email to me, and also via a public message on Bluesky, immediately below:

This is my English translation of the text in the Bluesky post:

Thanks, Federico!

The team has just corrected and improved the page to better present your ideas. As I already asked previously, simply let us know about the changes you desire on the page. We do not want to misrepresent your words.